Analysts say it’s hard to judge the Modi government’s track record on job creation as it has not released comprehensive employment data since 2016

Anil Gujjar arrived in India’s capital from a small village in the northwestern state of Rajasthan carrying nothing except a backpack and hopes of finding a good job.

The odds were not in his favour. In February, India’s railway system announced a national recruitment drive for the most menial positions in its hierarchy – helper, porter, cleaner, gateman, track maintainer, assistant switchman.

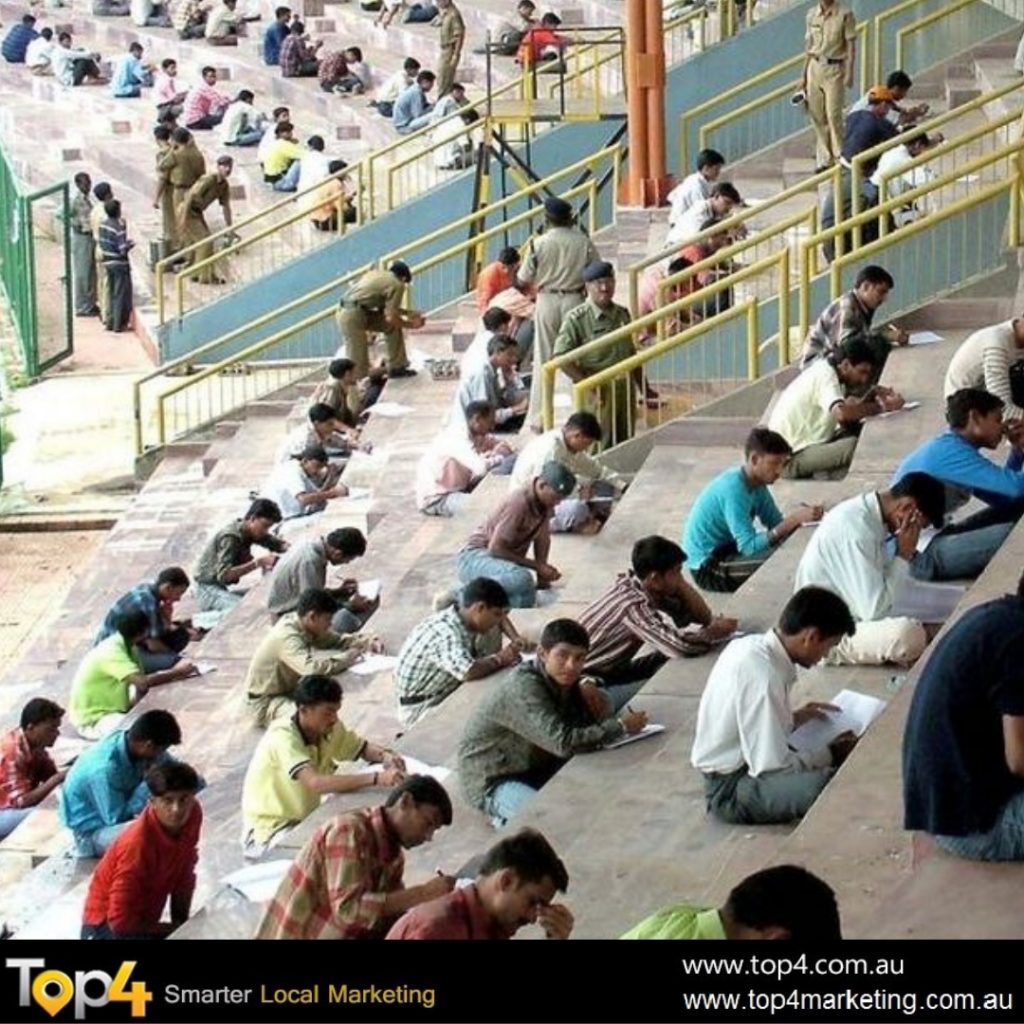

It attracted 19 million applicants for 63,000 vacancies.

Gujjar, the son of a farmer and the first person in his family to attend college, was one of them. At the test centre in Delhi where he took a mandatory exam in November, he looked around at hundreds of young men like him. Nearly all were college students or graduates. Some even had master’s degrees.

The railways recruitment effort is a potent symbol of India’s employment conundrum. The country is one of the fastest-growing major economies in the world, but it is not generating enough jobs for educated young people entering the labour force.

By 2021, the number of people in India between the ages of 15 and 34 is expected to reach 480 million. They have higher levels of literacy and are staying in school longer than any previous generation of Indians. The youth surge represents an opportunity, economists say, but only if they can find productive work.

The fate of India’s millions of jobseekers represents a major political liability for Prime Minister Narendra Modi as he seeks re-election this year. Modi came to power almost five years ago promising “development for all” and robust job creation. But his attempts to increase manufacturing and entrepreneurship have not succeeded in turbocharging employment.

“India is rapidly losing an opportunity,” said Mahesh Vyas, chief executive of the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a research firm in Mumbai that conducts a national employment survey. “We’re just arguing needlessly and endlessly rather than deploying all these young people coming into the labour market into productive work.” The result is a “slow and insidious crisis,” he said.

For many young Indian people, finding a job is an all-consuming task. An entire industry has sprung up offering “personality development” classes – a combination of basic English, social skills and interview preparation advertised as improving employability. Job scams are common, with fraudsters preying on the aspirations of those seeking work.

Ajit Ghose, an economist at the Institute for Human Development in Delhi, says India needs to generate jobs not only for fresh entrants to the workforce – who number 6 million to 8 million a year – but also for people who are working far less than they would be if they could get stable jobs that paid a decent wage. Ghose has calculated that India has at least 104 million “surplus” workers.

Judging the Modi government’s track record on job creation is hard because it has not released any comprehensive employment data since 2016.

Arvind Panagariya, an economist who served under the current government as vice chair of its policy planning agency, argued that no real assessment of the employment situation is possible until new data is released by the Statistics Ministry. Meanwhile, he said, his sense was that concerns about job creation are “overblown”, given India’s high rates of economic growth.

For India’s educated youths, searching for a job that meets their aspirations can feel like a marathon. At the test centre in Delhi, waves of applicants for the railway positions arrived three times a day, each weekday, from September until mid-December – a scene repeated at hundreds of exam centres across the country.

The flow of test takers was so large and consistent that it created its own miniature economy. One entrepreneur operated a makeshift storage locker from a truck parked outside. Since the applicants could not take anything inside the exam centre, he kept backpacks and phones for a fee of 50 rupees (70 cents). A vendor sold tube socks and ear buds on the pavement nearby.

The railway jobs on offer are junior but offer security and a comparatively good salary. The starting pay is 18,000 rupees (US$250) a month, plus there are perks such as free train travel.

Too anxious for chitchat, Gujjar declined to describe how he felt at that moment. “Ask me after I see the exam paper,” he said. The posts at Indian Railways held no appeal, he explained. “I just want a job.”

After taking the 90-minute computerised test, Gujjar strode through a blue metal gate with a smile of relief on his face. The exam was not as difficult as he had feared. It will be months before he knows whether he has beaten the odds, which are roughly 1 in 300. “If I get a job, it will be worth it,” he said.

Source: South China Morning Post